All your state are belong to us

April 25, 2015

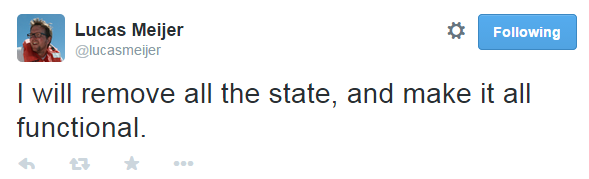

My colleague Lucas Meijer was recently making changes to a rather complex bit of code in IL2CPP, the VTableBuilder class, when he tweeted this:

I added the rather unoriginal response “All your state are belong to us.”

This started me thinking though, could it be true that our programs have been overrun with mutable state? Is mutable state something like an invading alien army, which has taken control? The code Lucas was modifying solves a complex problem in IL2CPP (it generates a representation of the vtable for a class in managed code that is used in the native translation of the code). But is that code more complex than necessary, due to mutable state?

More to the point, I wanted to answer the following questions:

- What is problematic mutable state?

- How do we correct problems with mutable state?

- Why can functional code solve the problems with mutable state?

What is mutable state?

I think that mutable state is relatively easy to define.

Mutable state: A sequence of bits stored in some type of memory (e.g. registers, non-volatile memory, volatile memory) which is written by one instruction and read by another instruction.

Usually, we introduce mutable state with an assignment operator. For example:

int answer = 42; // mutable stateBut all mutable state is not problematic. Variables must have some value (no pun intended), otherwise we would not use them so prevalently. Instead, we should define problematic mutable state.

Problematic mutable state: Mutable state which is stored at a scope too large to easily reason about.

The problems we have with mutable state are not really about the state itself, but more so about about the state transitions. Specifically, when the value of the of the state variable changes, do we notice that change? Do we handle all of the possible values? How does the program behave when the mutable state takes on an unexpected value? By keeping the scope of the mutable state small enough for us to reason about, we can either answer or eliminate these questions.

How do we correct problems with mutable state?

As consumers of software, what do we usually do to correct problems with mutable state? If one of our tools, say an IDE or operating system, starts to behave badly, we restart it, right? What does restarting the software actually do? Why does it usually make the software behave correctly? By restarting it, we are actually modifying the mutable state in the program to known good values. Those values might make sense, like 0 for an integer, or NULL for a pointer. Even if they are uninitialized values, the software can deal with (or ignore) them. It was started millions of times during its development, so the value of all mutable state when the program was started can be handled correctly. Effectively, we have set the mutable state to the start of a known scope. The scope might be very large, but when the scope starts the state values are not problematic.

As a programmer, I do the same thing. I control mutable state with various scopes, and I restart the scopes when I want to avoid the questions about mutable state (or at least, I should do this). For imperative programming in a object-oriented language, I think there are three levels of mutable state:

- Global or static variables

- Class or struct member variables

- Function local variables

I’ve been taught from an early age to avoid global and static variables if at all possible. Why? In the context of this discussion, they can easily represent problematic mutable state, because their scope is the lifetime of the process. It is not possible for the programmer to restart their scope without restarting the process. For most programs and programming languages, that is not an option, as the process is the program itself.

Class members are a bit easier to manage than global and static variables, since we have an idiom in object-oriented programming to restart their scope, the constructor. But I can still run into problems by exposing the mutable state from a class member to a larger scope. For example:

class employee {

public:

employee(const string& name)

: name_(name) {}

const char* getName() {

return name_.c_str();

}

private:

string name_;

};Does getName return a copy of the string stored in name_? (It does not.) What happens to the pointer returned if this instance of employee does out of scope? (It is a dangling reference.) These questions and many others occur because name_ represents mutable state in the employee class. By exposing it publicly, I have made it problematic mutable state, because it is no longer under the control of the scope for employee (its constructor/destructor pair).

Code like this is one of the reasons the tell, don’t ask principle is sometimes useful for object-oriented programming. However, this employee class could have a better API, mainly because of the exposure of problematic mutable state. We could improve the API and eliminate the problematic mutable state by returning a copy of the mutable state, like this:

class employee {

public:

employee(const string& name)

: name_(name) {}

string getName() {

return name_;

}

private:

string name_;

};Now the scope of the mutable state has changed, so that its scope is the same as the scope of the caller. The second version of this code just feels better. I think it is because we often have a natural tendency to avoid problematic mutable state.

Consider a function like this:

int& getAnswer() {

int answer = 42;

return answer;

}Immediately this function makes my skin crawl. It does the same for the compiler:

employee.cpp:14:12: warning: reference to stack memory associated with local variable 'answer' returned [-Wreturn-stack-address]

return answer;

^~~~~~

This is a clear case of problematic mutable state, since a reference to a local variable is returned. The memory location for that reference (on the stack) can be reused after the function returns; we have no guarantee that the value in that memory location won’t change. This case of problematic mutable state is so clear, the compiler even warns us about it. But it really is similar to the first iteration of the employee class above. By exposing mutable state to a scope too large, we make that mutable state problematic.

This problem is not restricted to memory access in native languages either. This C# code has a similar problem:

class employee {

private List<string> titles;

public List<string> Titles {

get { return titles; }

}

public employee(List<string> titles) {

this.titles = titles;

}

}By exposing a mutable collection publicly, the employee class here has introduced the possibility that other code could add or remove entries from that collection, thus changing the state of the collection in a way that the employee class does not expect. Again, this can be corrected with a better API design, as suggested by the .NET Framework Design Guidelines:

- DO NOT provide settable collection properties.

- DO use ReadOnlyCollection

, a subclass of ReadOnlyCollection , or in rare cases IEnumerable for properties or return values representing read-only collections

class employee {

private List<string> titles;

public ReadOnlyCollection<string> Titles {

get { return new ReadOnlyCollection<string>(titles); }

}

public employee(List<string> titles) {

this.titles = titles;

}

}All of these examples of problematic mutable state can be solved by better controlling the scope of mutable state. In this context “better” usually means:

- Make the scope of mutable state as small as possible.

- Avoid leaking the mutable state outside of that scope.

- Make a copy of the mutable state to change its scope where necessary.

In object-oriented programming, this concept is known as encapsulation. But in my experience, encapsulation can be difficult to get right, especially over the long lifetime of a given class. Instead, functional programming can help prevent mutable state by changing the question.

Why can functional code solve the problems with mutable state?

Functional programming can solve problems with mutable state by changing the question from “How do we manage mutable state?” to “Why do we have mutable state?”. Strict functional languages like Haskell eliminate almost all mutable state, making problematic mutable state difficult to introduce. Even in C# and C++ though, we can take a functional approach by using static or free functions and avoiding static and global data.

As long as these functions are small, we can limit the scope of the mutable state to something we can easily reason about. Once we know all of the possible values of the mutable state, and we can understand all of the code which causes transitions from one value to another, that mutable state is no longer problematic.

Functions which affect the state of only local variables, like pure functions in D, allow the compiler to have a built-in restart button. Since local variables (i.e. mutable state) are created at the start of each function and destroyed at its end, every call to a function resets the mutable state. So the same techniques for “fixing” problems with mutable state we use as consumers of software can be used as creators of software by taking a functional approach.