Learning loop unrolling

February 12, 2024

In the excellent Freakonomics Radio podcast series about physicist Richard Feynman (stop reading now an go listen to it!) I heard an interesting tidbit from Feynman:

Knowing the name of something doesn’t mean you understand it. (video)

After reading a recent blog post from Modular about loop unrolling, I realized that I know what loop unrolling is, but I don’t really understand it. This post is my journey to a deeper understanding.

The setup

I decided to start this deep dive with the matrix multiplication documentation for Mojo, to see how loop unrolling impacts the naive “matmul” algorithm.

I’m doing all of this on an M2 macOS machine, but the results should apply equally to x64 processors.

I’m using a few excellent tools:

I’ll be fiddling with this Mojo code, which depends on the Matrix type implemented in the documentation linked above, using elements of type DType.float32. You can find all the code I used for this exploration on Github.

alias N = 1024

fn matmul_naive(C: Matrix, A: Matrix, B: Matrix):

for m in range(N):

for k in range(N):

for n in range(N):

C[m, n] += A[m, k] * B[k, n]

def main():

var C = Matrix(N, N)

var A = Matrix.rand(N, N)

var B = Matrix.rand(N, N)

matmul_naive(C, A, B)

A.data.free()

B.data.free()

C.data.free()

The wrong path

Sometimes blog posts make it seem like the author knew what they were doing the whole time. For me at least, this is usually not the case. I’ll start by showing how I went down the wrong path.

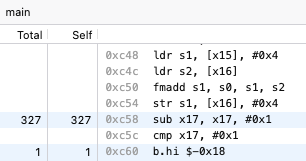

First, I compiled the code with mojo build, then used Ghidra to look at the assembly code. Most of the work here is done in this loop (which is the inner-most of the three loops):

LAB_100000c48

ldr s1,[x15], #0x4

ldr s2,[x16]

fmadd s1,s0,s1,s2

str s1,[x16], #0x4

sub x17,x17,#0x1

cmp x17,#0x1

b.hi LAB_100000c48

The third instruction - fmadd - is the key one here. It is doing one multiply and one add operation, all in one instruction, on 32-bit floating point values. After the mathematics, the loop counter in the x17 register is decremented, and the code jumps back to the top of the loop for the next iteration.

So, I wondered what would happen if I added the unroll directive to the outer most loop.

fn matmul_naive(C: Matrix, A: Matrix, B: Matrix):

@unroll (4)

for m in range(N):

for k in range(N):

for n in range(N):

C[m, n] += A[m, k] * B[k, n]

The Mojo compiler dutifully gives me four loops, with three additional copies of the assembly code loop shown above plus some setup and teardown code in between (I’ll avoid showing them here to save space). So this is loop unrolling, cool!

The code must be faster now, right? Let’s see what Hyperfine tells us. I benchmarked the implementation without unrolling against unrolling the loop 4, 8, 16, and 32 times.

Benchmark 1: ./matmul

Time (mean ± σ): 361.3 ms ± 3.1 ms [User: 342.3 ms, System: 2.0 ms]

Range (min … max): 357.3 ms … 368.2 ms 10 runs

Benchmark 2: ./matmul_unrolled4

Time (mean ± σ): 387.7 ms ± 1.7 ms [User: 369.3 ms, System: 1.9 ms]

Range (min … max): 384.9 ms … 389.9 ms 10 runs

Benchmark 3: ./matmul_unrolled8

Time (mean ± σ): 389.7 ms ± 5.2 ms [User: 373.5 ms, System: 1.7 ms]

Range (min … max): 376.6 ms … 394.3 ms 10 runs

Benchmark 4: ./matmul_unrolled16

Time (mean ± σ): 394.7 ms ± 1.5 ms [User: 376.3 ms, System: 1.8 ms]

Range (min … max): 392.4 ms … 396.7 ms 10 runs

Benchmark 5: ./matmul_unrolled32

Time (mean ± σ): 422.0 ms ± 2.4 ms [User: 403.4 ms, System: 1.9 ms]

Range (min … max): 416.3 ms … 425.6 ms 10 runs

Summary

./matmul ran

1.07 ± 0.01 times faster than ./matmul_unrolled4

1.08 ± 0.02 times faster than ./matmul_unrolled8

1.09 ± 0.01 times faster than ./matmul_unrolled16

1.17 ± 0.01 times faster than ./matmul_unrolled32

Huh? The code was faster before I started to fiddle with loop unrolling. In all cases, I made the code execute more slowly! I was very confused. Had I read to the end of the Mojo matrix multiply documentation, I would have noticed that unroll makes more sense on the inner loop than the outer loop. But I instead went on a hunt to better understand loop unrolling in other languages.

Thankfully, I stumbled across the ARM C++ compiler documentation for #pragma unroll](which is how C++ compilers spell @unroll). Check out this example:

void matrix_multiply(float ** __restrict dest, float ** __restrict src1, float ** __restrict src2, unsigned int n) {

unsigned int i, j, k;

for (i = 0; i < n; i++) {

for (k = 0; k < n; k++) {

float sum = 0.0f;

/* #pragma unroll */

for(j = 0; j < n; j++)

sum += src1[i][j] * src2[j][k]; dest[i][k] = sum;

}

}

}

It looks very similar to the naive matrix multiply implementation in Mojo. You can fiddle with this example on Compiler Explorer to see the impact of loop unrolling in C++. It got me to thinking - maybe I should try to unroll the inner-most loop in Mojo as well.

Getting it right

As the Mojo documentation for matrix multiplication suggests, forcing the inner loop to unroll does improve performance. Let’s get straight to the results from Hyperfine:

Benchmark 1: ./matmul

Time (mean ± σ): 362.0 ms ± 4.1 ms [User: 341.3 ms, System: 1.8 ms]

Range (min … max): 356.0 ms … 371.9 ms 10 runs

Benchmark 2: ./matmul_unrolled4

Time (mean ± σ): 128.2 ms ± 3.9 ms [User: 108.6 ms, System: 1.6 ms]

Range (min … max): 124.4 ms … 143.4 ms 21 runs

Benchmark 3: ./matmul_unrolled8

Time (mean ± σ): 116.2 ms ± 4.1 ms [User: 98.3 ms, System: 1.6 ms]

Range (min … max): 102.8 ms … 119.4 ms 24 runs

Benchmark 4: ./matmul_unrolled16

Time (mean ± σ): 114.3 ms ± 3.9 ms [User: 95.3 ms, System: 1.6 ms]

Range (min … max): 104.1 ms … 125.7 ms 22 runs

Benchmark 5: ./matmul_unrolled32

Time (mean ± σ): 114.3 ms ± 2.9 ms [User: 95.3 ms, System: 1.6 ms]

Range (min … max): 109.3 ms … 121.7 ms 23 runs

Summary

./matmul_unrolled32 ran

1.00 ± 0.04 times faster than ./matmul_unrolled16

1.02 ± 0.04 times faster than ./matmul_unrolled8

1.12 ± 0.04 times faster than ./matmul_unrolled4

3.17 ± 0.09 times faster than ./matmul

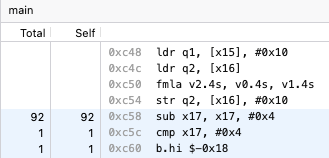

Now this is cool! The unrolled versions all ran about 3 times faster than the naive implementation. But this is not really a complete understanding. Why is the code so much faster with inner loop unrolled? Let’s have a look at the assembly code for that unrolled inner loop.

LAB_100001724

ldr q1,[x15], #0x10

ldr q2,[x16]

fmla v2.4S,v0.4S,v1.4S

str q2,[x16], #0x10

sub x17,x17,#0x4

cmp x17,#0x4

b.hi LAB_100001724

Can you spot the difference? It took me a while, so let’s look at the normal code and the unrolled code side by side.

Normal Unrolled

================== | ======================

ldr s1,[x15], #0x4 | ldr q1,[x15], #0x10

ldr s2,[x16] | ldr q2,[x16]

fmadd s1,s0,s1,s2 | fmla v2.4S,v0.4S,v1.4S

str s1,[x16], #0x4 | str q2,[x16], #0x10

sub x17,x17,#0x1 | sub x17,x17,#0x4

cmp x17,#0x1 | cmp x17,#0x4

b.hi LAB_100000c48 | b.hi LAB_100001724

Check out the multiply and add operation, it is spelled differently - fmla. This an ARM instruction that does floating point multiply and add, but on a vector of four values, rather than a scalar of one value. Also, notice the subtraction in register x17 - it now iterates the loop counter by 4, instead of 1. Each time through the unrolled loop, we get four operations, not just one.

We can confirm this by running the Samply profiler:

samply record ./matmul

samply record ./matmul_unrolled4

While Samply does not report exactly four times fewer calls to the loop decrement, it is pretty close. The unrolled inner loop is doing significantly fewer iterations.

Compilers ❤️ Processors

What is really going on here?

By telling the Mojo compiler to unroll that inner loop, we’re giving it a better chance to use the available hardware. ARMv8-A processors (like the ones in my Mac) have 32 registers that are 128 bits wide. The “S” prefix from the normal assembly code means “Word”, or a 32-bit value. The “Q” prefix from the unrolled assembly code means “Quadword”, or a 128-bit value.

In this example our data type is 32-bit floating point values, so the normal example is not using all of the available register space. It is only using 32 bits (one-fourth) of registers s0, s1, and s2 during each loop. But with the unrolled loop, the compiler is able to notice the chance to “vectorize” the code, and use the full width of each 128-bit register, where it can put four 32-bit floating point values side by side, and then use the fmla instruction to compute the multiply and add operation on all four together. The ARM documentation explains the interesting .4s syntax on each of the arguments to fmla.

Vn.4S - 4 lanes, each containing a 32-bit element

So the compiler is able to more efficiently use the registers available on this process.

Why do we need to manually unroll the inner loop to allow the compiler to see this possible optimization? I’m not entirely sure. I suspect the compiler has some limited budget for time spent on loop analysis. After all, we want our to to compile fast as well.

Where to next?

This example is certainly not the best possible matrix multiplication algorithm. The Modular documentation linked above goes into much more detail about techniques to improve its performance. But it does give us a fun little insight into loop unrolling though, and specifically into how it is implemented in Mojo. I wonder what this example looks like in other languages.

Appendix

Notice in the benchmarking data for the unrolled inner loop, we get slightly better performance as we unroll that inner loop more and more. Skipping by 8, 16, and eventually 32 iterations each yields small marginal gains - but why?

The assembly for the @unroll(32) case provides a hint:

LAB_1000016dc

ldp q1,q2,[x17, #-0x40]

ldp q3,q4,[x16, #-0x40]

fmla v3.4S,v0.4S,v1.4S

fmla v4.4S,v0.4S,v2.4S

stp q3,q4,[x16, #-0x40]

ldp q1,q2,[x17, #-0x20]

ldp q3,q4,[x16, #-0x20]

fmla v3.4S,v0.4S,v1.4S

fmla v4.4S,v0.4S,v2.4S

stp q3,q4,[x16, #-0x20]

ldp q1,q2,[x17]

ldp q3,q4,[x16]

fmla v3.4S,v0.4S,v1.4S

fmla v4.4S,v0.4S,v2.4S

stp q3,q4,[x16]

ldp q1,q2,[x17, #0x20]

ldp q3,q4,[x16, #0x20]

fmla v3.4S,v0.4S,v1.4S

fmla v4.4S,v0.4S,v2.4S

stp q3,q4,[x16, #0x20]

sub x0,x0,#0x20

add x17,x17,#0x80

add x16,x16,#0x80

cmp x0,#0x20

b.hi LAB_1000016dc

There are eight fmla instructions, set up in four pairs, where each instruction in a given pair is using different result registers. I’m not sure how the Apple M2 implementation works, but I suspect it can take advantage of hardware-level parallelism here, and exec both of the fmla instructions in a pair at the same time. It sounds like I have more to explore!