Scalability in a Functional Language

April 23, 2013

I’ve heard a lot of buzz recently about functional programming languages. Many well-respected developers and speakers have been making the case that functional languages will allow better use of multiple processors, because functional languages prevent data sharing.

I have very little experience with functional languages, so I wanted to try this for myself. Do functional languages make implementation of algorithms for multiple processors easy? As a novice functional developer, can I implement a CPU-bound algorithm that scales linearly using a functional language with less effort than I can in an imperative language?

TL;DR

Functional languages are not a panacea for multi-processor development. They prevent data sharing by default, and require the developer to think about shared data when it is used. However, development of a scalable, mulit-processor algorithm is still difficult. It requires intimate knowledge of both the problem domain and the development tools.

The Problem

I’ve been aware of this problem from a young age - sharing. Imagine a large pile of Legos©:

If just one child is playing with these Legos©, we don’t have any problems. Maybe even two or three children could play together here, but what about eight, or ten, or twelve children? Soon, two or more children will want to use the same block. The ensuing contention will slow down the entire building process.

Implementation of an algorithm which scales to multiple processors faces the same problem. If any data (Legos©) are shared among the processors, the contention will cause the program to take longer to complete. As more processors become involved, some capability of each processor will be wasted, waiting for shared data.

Ideally, an implementation should scale linearly, that is, the wall-clock time to execute it with two processors should be half the time to execute it with one processor. The time to execute it with four processors should be half the time required to execute it with two processors. In practice, this is difficult to achieve. Many implementations scale linearly up to a few processors, then suffer from increased contention as more processors are used.

In most imperative languages, data is shared between threads by default, often making data sharing difficult to find and eliminate. In functional languages data is not shared by default, giving the promise of writing scalable algorithms with less difficulty.

The Challenge

I attempted to implement a CPU-bound algorithm in both C++ (imperative language) and Clojure (functional language). My goal was to compare the scalability of both algorithms using shared-memory parallelism. I did not attempt to compare wall-clock performance.

I choose to implement an algorithm to categorize all of the two-player Nash games of a given size as I described in a previous post for a few reasons:

- I know this algorithm well

- I already have a C++ implementation

- The algorithm involves no data sharing

The Tools

I have chosen to use C++ as the imperative language. My implementation depends on the Boost and Intel Threading Building Blocks libraries. The source code is available here.

I have chosen Clojure as the functional language. I am not using any additional libraries. The source code is available here.

The Disclaimer

I have some experience with C++ development. I have effectively no experience with Clojure development. I am rather certain that an experienced Clojure developer could provide a better implementation than I have. If you have suggestions to improve my implementation, please let me know! I would like to improve the implementation so that the results of this study can be more accurate.

The Setup

I profiled both implementations on a Windows 7 64-bit machine with two Intel Xeon X5675 processors. I ran each implementation using between one and twelve threads. For each thread count, I ran the implementation five consecutive times, and averaged the wall-clock run time for each. I used games of size 6x6 for the C++ implementation. The Clojure implementation used signifigantly more memory than the C++ implementation, so I was unable to complete a run with games of size 6x6 without exhausting all of the memory on the machine. Instead, I used games of size 5x5 for the Clojure implementation.

The DOS batch file used to run the implementations is available here.

The Results

The C++ implementation almost achieved linear scalability, which was a surprising result. The Clojure implementation demonstrated consistently sub-linear scalability up to six threads. For more than six threads the wall-clock time for the execution was effectively unchanged.

Scalability#

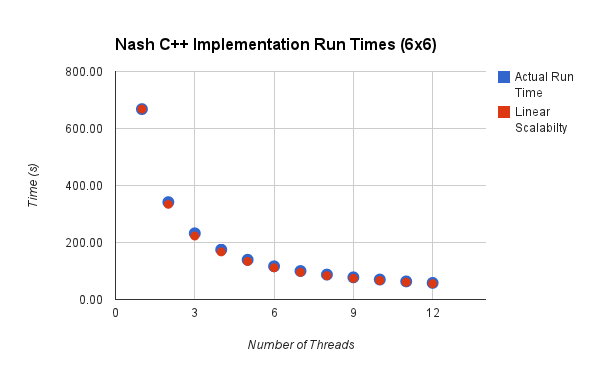

The chart below shows the scalability of the C++ implementation.

The actual run time is only slightly worse than linear scalability. I did not expect the implementation to be this good. I suspect that most of the scalability comes from the Intel TBB library implementation. As we’ll see later, the C++ implementation has very few cache misses, which probably improves the scalability of the implementation.

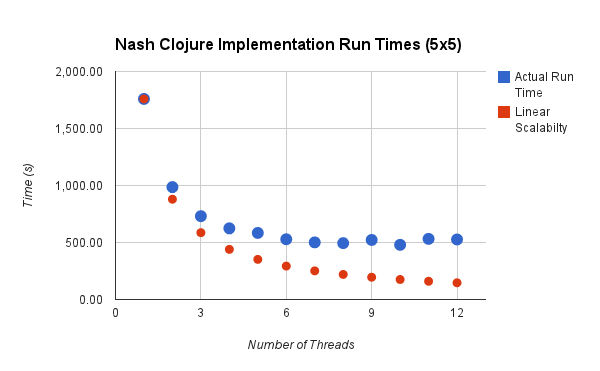

The chart below shows the scalability of the Clojure implementation.

This implementation gets nearly linear scalability for two and three threads, then tails off and fails to improve after six threads, effectively wasting CPU resources for any more than six threads. Since the algorithm requires no data sharing, and the Clojure implementation does not have any shared data, this seems like a surprising result. I believe that I can explain the problem though.

Memory Usage#

Once the execution of each algorithm got started, I compared the memory usage, measuring it with Process Explorer. For this test, both implementations used eight threads. The difference is dramatic. The C++ implementation used 1.7 MB of memory, but the Clojure implementation used 3.3 GB of memory. Keep in mind that the C++ implementation was running with games of size 6x6, whereas the Clojure implementation was operating on a much smaller problem, games of size 5x5. So although the algorithm requires no state (other than the results), the Clojure implementation was clearly using far too much memory. This memory usage pattern lead me to consider that the cause of the scalability problem in the Clojure implementation may be related to cache misses.

Cache Misses#

I used Intel VTune Amplifier XE 2013 to profile the performance of each implemenation running with eight threads. The Intel Xeon X5675 processor has 2MB of L2 cache and 12 MB of L3 cache, so the entire address space used by the C++ implementation can fit into the L2 cache. I would expect very few misses for the L2 cache, and almost no misses for the L3 cache with the C++ implementation. Since the Clojure implementation used signifigantly more memory, I expected to see many more cache misses.

Using the profiling guide here, I computed the percent of cache misses using these formulas:

- L2: (((MEM_LOAD_RETIRED.LLC_UNSHARED_HIT * 35) + (MEM_LOAD_RETIRED.OTHER_CORE_L2_HIT_HITM * 74)) / CPU_CLK_UNHALTED.THREAD) * 100

- L3: ((MEM_LOAD_RETIRED.LLC_MISS * 180) / CPU_CLK_UNHALTED.THREAD)* 100

and I obtained the following results:

| C++ | Clojure | |

|---|---|---|

| L2 cache miss percentage | 0.95% | 8.16% |

| L3 cache miss percentage | 0.01% | 4.19% |

I believe that these results explain the difference in scalability. The Clojure implementation spent signifigantly more time dealing with cache misses. The C++ implementation effectively never missed L3 cache, meaning that it could completely avoid going to main memory. Althougth the Clojure implementation has no real data shareing, it seems to suffer from false sharing, often exhausting the L2 and L3 caches.

Suppose that we attempted to fix the Lego© contention described above by separating some of the blocks into groups, and giving each pair of children one group of blocks to use. Most of the blocks could still be in one pile that the children could access, but we’ll have an adult manage that pile, and make sure the only one or two children can takes blocks from it at a time.

In the C++ implementation, the children have enough blocks in their local pile to keep them happy, very few children go to the larger pile and ask permisson to use blocks. However, in the Clojure implementation, the children are going to the larger pile much more frequently. As the number of children increases, the adult managing the pile has more work to do, and we often have a line of children waiting for access to the large pile.

Unsurprisingly then, the overall time required to build with the blocks increases. At some point, adding additional children to the job will not make the overall time any better.

The Next Challenge

I don’t believe that the Clojure implementation should need to use this much memory. I suspect this is caused mainly by my lack of experience with Clojure development. So the next step is to find the part of the Clojure implementation using that memory, and replace it. Then I expect the implementation to scale much better.